Treasure San Jose

History of the Galleon Almiranta "San Jose"

Treasure: San Jose

SOUTH SEA EXPEDITIONS

The discovery of the New World by Christopher Columbus was a turning point in world history. His discovery ushered in an age of exploration and conquest that made Spain the most powerful country in the world. The flow of silver, gold and precious stones that started out as a trickle, became a torrent that brought about an economic revival throughout all of Europe.

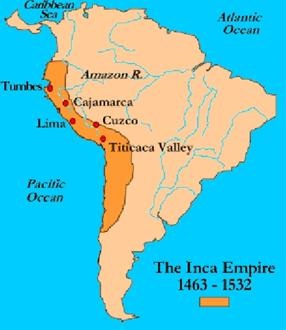

The conquest of the Incas by Pizzaro in 1532 left Spain in control of vast regions of South America with the west coast being one of Spain's richest possessions. What was once the Vice-Royalty of Peru are today the countries of Chile, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia and Venezuela. Throughout the colonial period, the Spaniards located and exploited rich silver and gold mines throughout the Andes Mountains. These sources were so rich that various mints were established over the centuries for the

production of coinage. Mints at Lima, Cuzco, and Potosi produced coinage that became the national currency for many nations of the world at that time, including the American colonies and eventually the early United States.

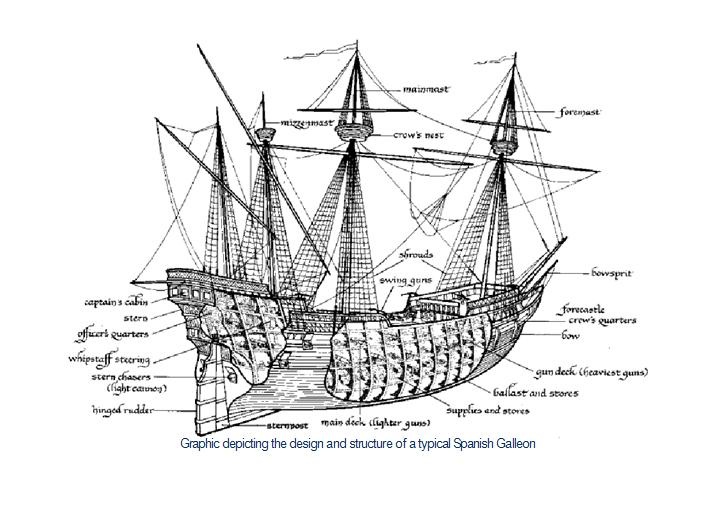

As these sources of precious metals were exploited, the treasure, in coin, ingot and jewelry form, was loaded aboard ships of the

"South Seas Armada". These ships would travel the western coast of South America to pick up and deliver goods to ports along the coast. The principal route taken by these galleons would see them start at the south and stop at ports along the coast while making their way to Panama for final delivery of all the treasure that had been collected from the mints and mines. From there the treasure would be transported across the isthmus by mule train where it would be picked up by the Tierra Firme Armada and shipped back to Spain. Over the centuries, hundreds of ships were lost along the west coast of South America as they sailed the coast laden with treasure and other merchandise.

HISTORY OF THE SAN JOSE

The "GRAND OLD LADY" of the South Seas Armada, the Galleon Almiranta SAN JOSE, was christened on April 25, 1611 together with her sister ship the SANTA ANA. With a displacement of approximately 700 tons and a cost of 249,180 pesos to construct, the SAN JOSE was later downgraded to Almiranta (V. Lohmann, p. 89).In 1631, the year that the SAN JOSE sank, all of the ships in the South Seas Armada were in deplorable shape. At this time, there were only three Galleons and one Patache (200-ton ship) in the fleet. All were old ships, of which the SAN JOSE was the oldest.

The ships were loaded in Callao, the port of Lima, Peru, and set sail on the 31st of May 1631. She was carrying the precious cargo of important people, 416 cases weighting 51 tons of silver coins known as Reales de Ocho, "pieces of eight". Most of the silver had come from the rich deposits at Potosi, a virtual "mountain of silver" located in what is now Bolivia. Included in the contraband cargo was a small, but not insignificant, amount of gold bullion in the form of gold tejos (disks) and gold chains.

The SAN JOSE alone was carrying, in "official" manifestedcargo, approximately 2 million pesos in treasure (Audiencia de Lima, Legajo 44, Seville, Spain). "It is said that when the Fleet left port, it was carrying more than 8 million pesos in silver and gold"

(Diary of Lima, J. Suardo and Audiencia de Lima, Legajo 43). On this particular voyage, the Priest Alonso Messia, the Procurator General of the Province for the Company of Christ (Jesuits), was a passenger of the Capitana, the SAN JOSE also sailed with a compliment of 106 crewmen and with at least that many passengers. When the Almiranta del Mar del Sur (the South Seas Fleet) left port heading North along the western coastline of South America, the voyage was expected to last about 2 weeks until docking at Panama City. There, her cargo would be off loaded and transported to Portobello, Panama, on the Atlantic

side.

LOSS OF THE SAN JOSE

During the Spanish Colonial period, navigating was the exclusive domain of the pilot, who usually depended upon personal experience and intuition rather than upon charts (Diving for Sunken Treasures, p. 50). In the 300-year history of the Spanish in the New World, an estimated one-in-eight ships sank (Smithsonian, Jan; 1987) of which the majority are in shallow water.

Most of the losses were due to a combination of bad weather, poor navigation, charts and lack of competent and well-trained pilots. In the case of the SAN JOSE, the pilot sailed into a previously unknown shoal off the coast of Panama. In a letter from the Viceroy of Peru (Count of Chinchon) to King Phillip IV of Spain (Lima 43, Dispatches of the Viceroy of Lima, 1630—1632), it was stated that; "at 40 leagues from that town (Panama City) near the island...and in front of 'Cabo de Garachine', during the night of the 17th of June 1631, voyaging the small Armada in which went the silver of His Majesty and of particulars (individuals), the Almiranta SAN JOSE touched the bottom on a shoal, in the heavy current, in such a way that it was lost..". "...the Almiranta touched bottom in 5 and '/2 braces (approximately 35 feet) of water, and all who were registered aboard were saved except for one man who drowned while attempting to save a case of silver coins" (Diary of Lima, J. Suardo).

Of the many declarations found in the Archives in Spain, one of the more comprehensive was made by a young Alferez (Ensign) named Diego Fernandez de Madrid. This naval officer was stationed on board the San Jose when it struck the shallow and foundered. Testimony of Alferez Don Diego Fernandez de Madrid; "We left Callao on the Almiranta San Jose on the 31st of May 1631 at 10 PM. After a few days sailing we arrived off Manta where we sent some dispatches ashore, as per our instructions, and we continued the next day enroute to the Port of Perico, near Panama City. On the 17th of June in the afternoon (2 PM) we came in sight of Punta de Garachine and Islas del Rey, and the canal located between them and the mainland. We sailed onward, with the Capitana and Patache launch ahead, and with our Almiranta following. We navigated in sight of each other by day and by top mast light of the Capitana at night. Each day, in the morning, the Capitana spoke with the Almiranta. Each afternoon, we repeated this performance, asking our name and going through a predetermined set of identifying maneuvers. From on board the Almiranta we could see as we approached the above-said islands that the launch (Patache) of the Capitana was sent out ahead. This launch was commanded by Captain Juan Romero and its purpose was to sound the depths ahead and keep an eye out for enemy as was the custom in these seas.

Likewise, the launch lighted his, as was the instruction for this place. Going along like this with very light winds, the Capitana changed course to the seaward (west) and the Almiranta followed. After a while, the Capitana again tacked, resuming its original course for Perico. The Almiranta followed but was somewhat slower to respond to this maneuver and,

upon resuming course, found itself one-half league astern and more toward the mainland. They continued this way until about 10 PM. All during the darkness the pilot had taken continuous soundings with the sounding lead. At the above time, or close to it, we heard a cannon fire from the Capitana, which signal in these waters meant the fleet was to anchor.

Since the Almiranta was in 25 brazas of water (about 138 feet) and the Capitana still one-half league ahead, the anchoring procedure was delayed some in an attempt to close the distance between the two ships. As the Boatswain stood at the anchor station with the drop line in his hand, the ship suddenly struck bottom with no warning. Upon striking, I heard the 1st Pilot order the anchor dropped, and it was done. As the anchor line payed out the ship struck bottom several more times with more force than before. Our evident risk was very grave and we fired a cannon and followed this with two more, than fired some muskets, all to alert the Capitana of our great peril.

The Capitana responded with a shot, signifying they were coming to our aid. We tried to launch our small boat into the water, and it appeared to this testifier that the Capitana was doing the same. In a short time the Capitana's small boat was seen coming toward the Almiranta and this testifier gave notice of this to the others who stood in the ship's waist together.

Meanwhile, in the attempt to launch the Admiral's boat, this effort was being hampered by the irregular rising and falling of the ship. In addition to this, the waters coursing up to the boat station were resulting in the block and tackle guiding the boat slipping. When it was finally done, the boat was tied off astern.

By now the water had come into the hull and had reached the hatchways, and the ship now layon its port side. We then cut down the masts in an effort to stabilize the hull. Because the hull was now full of water and lying on its port side the people all fled to the starboard side and sought refuge on the foremast or the bowsprit. They stood in this plight, signaling the Capitana with torches, until 5 AM. At this time we saw another boat coming from the Capitana, and they also were having a hard time of it due to the great current here. Then we saw the gondola coming with many rowers bending hard to make the trip, and it was the first to reach our ship. With the aid of these two boats all of the people were transferred to the safety of the Capitana, which effort took most of the day.

In the meantime, I went in the boat with the General, Admiral, and Pilot to secure a buoy to the main anchor of the wreck in case the hull broke up. The Pilot sounded all around the stranded ship and said that this is the only place on all of the shallow where the ship could have struck for all around there is sufficient water for ships of greater port than the

Almiranta.

The next day at sunup, the hull of the Almiranta was nowhere in sight. The General ordered the Pilot to raise anchor and proceed on his way to Perico. In the meantime, he sent out a launch and Gondola to buoy the bottom of the ship where most of the silver must still lay. It took us five hours to find it and the General sent three good swimmers down and they recovered 19 bars of silver among the many boxes of mercury which could be seen laying on the bottom below. Afterward, he gave five men and a guardian on the Gondola instructions to remain anchored to the Plan Deck until help could be sent back. He left them with extra anchors and provisions for eight days, then we departed in search of the Capitana.

When we were approaching the principal port of Isla del Rey, we sighted the Capitana and the three decks of the Almiranta drifting along with the currents. The General dispatched two of the launches with a long cable and anchors to row the remains of the hull into shore, taking care to find a clean place where it could be salvaged with ease. Many cannon could be seen on its decks and some felt much of the treasure must still be between decks. The General then went on toward Perico. Before arriving to this port, he sent his personal launch ahead to inform the President and Officials of the disaster and the great need for bergantines, divers, carpenters, and others to affect the salvage on the shallows of Garachine. I went ahead in this boat and gave the notices. Once we had assembled and loaded the salvage fleet, we went on with the said General

and the President of Panama to the shallow where the bars lay. Afterward, we returned to Las Islas del Rev where the decks of the Almiranta were anchored with the bronze artillery and proceeded to salvage it. Of the 28 pieces of artillery on board, 25 were recovered.

Later, the General returned to the Shallow of Garachine with the Almiranta's Pilot Juan de Medina and they searched the entire shallow with five of the best divers and God was served for they came across the main pile of boxes of Reales. In two hours they were able to bring up 87 boxes and by the end of three days they had recovered 202 boxes, many bars, sacks of loose coins, mercury treated virgin silver pinas, and fabricated silver items along with many other things. In all, the salvage effort amounted to over 1,200,000 pesos. This caused much happiness in the streets of Piru and Panama."

The coinage of Spain, once restricted almost exclusively to domestic circulation, ultimately became an international currency. This did not happen immediately, however, as the metal recovered from mines in America was usually shipped to the mother country in the form of ingots or crude, temporary coins called macuquinas.

Known in English as “cobs,” these coins were made by simply refining the ore to slightly over 90% fineness, rolling it like cookie dough into a rod shape, and then slicing off pieces to form crude flans. These were trimmed with scissors to the prescribed weight and coined by the ancient hammer method. One die was mounted on an anvil, the flan was placed atop it, and the other die was suspended above the flan with tongs. A heavy blow or two from a sledge hammer impressed the design into both sides of the flan to form the coin. Given their crude method of manufacture, it’s not surprising that cobs are usually found irregularly shaped and with only partially visible designs.

Cobs, like the ingots that accompanied them from America to Spain, were simply a means of accounting for the silver and gold extracted from the colonial mines. This was critical, as the king was entitled by law to twenty percent of the treasure, the “royal fifth,” which was paid to him as tribute. Most cobs were melted upon arrival in Europe and recoined into more conventional issues. Those which have survived intact were almost certainly recovered from the wrecks of ships bound for Spain.The minting of cobs ended by the middle of the 18th Century.

The Spanish silver coins most familiar to generations of Americans were the “Pillar” types, introduced in 1732 to replace the crude cobs and minted for the next forty years. These coins were of modern manufacture, being produced by a screw press. Their round, almost uniform planchets and rich designs made them immediately recognizable throughout Europe and America.

SALVAGE OF THE SAN JOSE

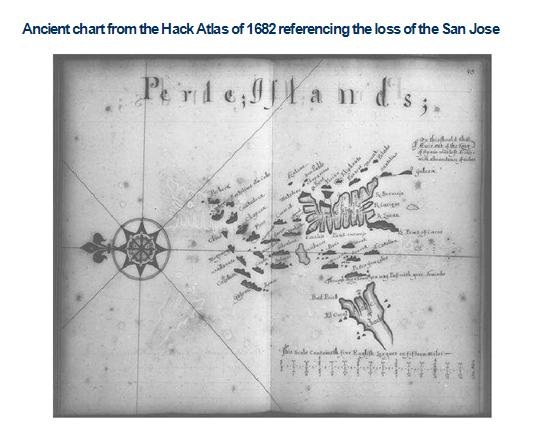

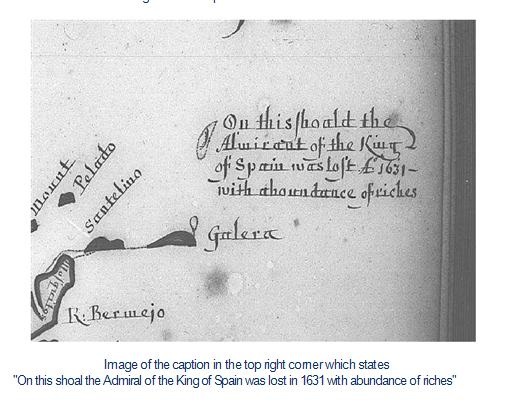

The material translated below is from the Archives of the Indies in Seville, Spain. This original manuscript is badly worn, and part of the upper right side is missing. However, the essence of the translation into English is as follows:

Compiled by Royal Judge Doctor Don Fernando Suarez de Patino before Royal Notary Alonso Jimenez de Ochoso;

The dated information has been provided by Officials under Captain General Don Bernadino Hurtado de Mendosa, and concerns efforts made by various people to salvage the treasure of His Majesty and that of the private merchants. This includes artillery, cannon balls, and ship's hardware on the galleon San Jose of the South Seas Armada. This ship was lost on a shallow East-West with Punta de Garachine and WNW- ESE with Isla Galera at the mouth of the canal formed by the Islas del Rey and the mainland.

It sank Tuesday night around 9:30 PM on 17 June 1631. In registry (according to a summary carried in the pocket of the Silver Master) the ship carried 1,417 silver bars. What has been brought up to this day and presented before this testifier is 1,150 silver bars. This leaves 267 not salvaged. The Almiranta also carried 416 boxes of 8 reales silver coins, of which 213 have been brought up (leaving 203 not salvaged). Of His Majesty's account of 107,000 some 73,436 have been recovered in talegos (canvas money sacks, usually containing 1000 pesos in coins). In addition, more than 1,500 marcos (one marco = 8 Spanish ounces, almost equal to an Avoirdupois ounce) of fabricated silver items have been brought up, along with 51 pinas (castings of retorted mercury refined silver amalgam, some in the shape of a pineapple). Of this amount 27 belonged to His Majesty, whose Royal Account in silver bars and reales has now been satisfied.

That salvaged material belonging to the merchants has been prorated (losses were evenly distributed on a prorated basis) and each has been satisfied, with little loss sustained of the 28 bronze cannon which the galleon carried, 25 have been recovered. This leaves one saker and two quarter cannon. Likewise, over 1,000 cannonballs have been saved and an indeterminable amount of ship's hardware and rigging. All of this was accomplished without delaying the return of the Capitana galleon to Callao with masts and spars for new ships, or the loss of time for the Tierra Firme Galleons at Porto

Belo.

CARGO OVERVIEW

To better understand the true extent of the amount of treasure carried by the SAN JOSE, several events with regard to the Capitana of the fleet, a ship called NUESTRA SENORA DE LORETO, must be reviewed. The Capitana of the fleet was delayed from setting sail in 1631 after carpenters, who upon inspection observed that the ship was in poor condition, was grossly overloaded and sitting so low in the water that in no way was she in any condition to sail, much less do combat if attacked. Because the Capitana would be carrying the Marquis de Gualcazara along with a contingent of other very important people, she had to be safe to sail.

Consequently, the Count of Chinchon (Viceroy of Peru) ordered the Capitana lightened by transferring a large portion of her cargo to the SAN JOSE which was already overloaded with her own registered cargo and contraband. This transfer of cargo was hastily performed just before departure of the fleet to Panama. Records indicate that this cargo was not recorded on

the official manifest of the San Jose and is not accounted for in survivor testimony. Many tons of treasure would have had to be transferred from the Capitana to have any noticeable effect on her overall stability. Since the SAN JOSE’s lower hold had already been loaded with her own cargo, the treasure from the Capitana would have had to be stored in the upper decks.

Historical evidence strongly indicates that the Capitana cargo represents a large and undocumented portion of the treasure that remains to be recovered. The ships were loaded in Callao, the port of Lima, Peru, and set sail on the 31st of May 1631. She was carrying the precious cargo of important people, 416 cases weighting 51 tons of silver coins known as Reales de Ocho, "pieces of eight". Most of the silver had come from the rich deposits at Potosi, a virtual "mountain of silver" located in what is now Bolivia. Included in the contraband cargo was a small, but not insignificant, amount of gold bullion in the form of gold tejos (disks) and gold chains. The SAN JOSE alone was carrying, in "official" manifest cargo, approximately 2 million pesos in treasure (Audiencia de Lima, Legajo 44, Seville, Spain). "It is said that when the Fleet left port, it was carrying more than 8 million pesos in silver and gold" (Diary of Lima, J. Suardo and Audiencia de Lima, Legajo 43).

On this particular voyage, the Priest Alonso Messia, the Procurator General of the Province for the Company of Christ (Jesuits), was a passengerof the Capitana, the SAN JOSE also sailed with a compliment of 106 crewmen and with at least that many passengers. When the Almiranta del Mar del Sur (the South Seas Fleet) left port heading North along the western coastline of South America, the voyage was expected to last about 2 weeks until docking at Panama City.

There, her cargo would be off loaded and transported to Portobello, Panama, on the Atlantic side. During the Spanish Colonial period, navigating was the exclusive domain of the pilot, who usually depended upon personal experience and intuition rather than upon charts (Diving for Sunken Treasures, p. 50). In the 300-year history of the Spanish in the New World, an estimated one-in-eight ships sank (Smithsonian, Jan; 1987) of which the majority are in shallow water. Most of the losses were due to a combination of bad weather and lack of competent and well-trained pilots. In the case of the SAN JOSE, the pilot discovered a previously unknown shoal off the coast of Panama.

In a letter from the Viceroy of Peru (Count of Chinchon) to King Phillip IV of Spain (Lima 43, Dispatches of the Viceroy of Lima, 1630—1632), it was stated that "at 40 leagues from that town (Panama City) near the island...and in front of 'Cabo de Garachine', during the night of the 17th of June 1631, voyaging the small Armada in which went the silver of His Majesty and of particulars (individuals), the Almiranta SAN JOSE touched the bottom on a shoal, in the heavy current, in such a way that it was lost..". "...the Almiranta touched bottom in 5 and '/2 braces (approximately 35 feet) of water, and all who were registered aboard were saved except for one man who drowned while attempting to save a case of silver coins" (Diary of Lima, J. Suardo). In the aforementioned document, it is stated that of "1417 (registered) bars, recovered are 1150 bars, so that only 267 are missing. Several accounts state a total cargo of 416 cases of pesos of Reals were on board (2500 pesos per case). 213 cases were reported salvaged and 73,436 pesos (pieces-of-eight)...of which 107,000 pesos have been salvaged."

Continuing with the account, recovered was "...more than 1500 silver marcos (value equals 7 pesos, 6 reales per marco, each marco weighs 1/2 pound) and 51 pinas (small bars) Royal Treasure inreales and bars is known and is stated at the end of this testimony". The letter also states, "Of the 28 pieces of artillery that the galleon carried, 25 are salvaged, only a shaker, and two quarters (types of cannons) are missing". A letter from Capitan-General Bemadino de Mendoza to the

Viceroy of Peru states, "...missing are more than 400,000 pesos in registered (cargo) from the manifest...".

A later letter which the Royal Officers of Panama City sent to the King, dated September 21, 1631 (Contaduria 1485A);

"...from the over 1 million and 800,000 pesos in the Almiranta on account of particulars, about 1,400,000 pesos have been salvaged".

It has become obvious that a great deal of contraband existed on the SAN JOSE; "and it is estimated and taken for certain that a large quantity of worked silver, gold, and other valuable things that were loaded aboard by His Majesty and what individuals carried aboard will be lost". In a letter from the Viceroy of Peru to King Phillip IV, (Letter 1, bundle 34, Legajo Lima 43): "The damage this loss for the vassals of His Majesty V will be considerable, as for much skill be needed or the sea will keep some part...pinas (small bars), Plata labrada (worked silver), gold tejos (disks), and gold chains I am sure there will be a lot on which Your Majesty has all rights to take them since they go without manifest and without quintar (Royal Fifth Tax)". "...with all this, the loss has been great, as the part that was not registered, it is clearly understood, was great"

(Letter from Captain-General Bemadino de Mendoza, dated September 8, 1631).

The following are two accounts of passengers who traveled aboard the SAN JOSE and manifested their contraband after the shipwreck.

PETITION: "The official, D. Juan de Otalora, lawyer in the Royal Courts in the City of the Kings (Lima, Peru) said: because of the hurry that we had when we embarked aboard the galleon SAN JOSE, Almiranta, I was unable to register nor manifest two large serving trays, one being glided in gold and the other plain silver and two large dishes, one large salt shaker made of three pieces which is gilded and two gilded cups and a large gilded pitcher with its platter and another smaller pitcher of silver and two dozen spoons and two ladles and another gilded salt shaker and other things of silver of my service. All of these came in a case of wood with my mark. Also a gold chain that weighted nineteen pounds made of solid gold more or less, with five loops of intricate detail. A necklace of diamonds bathed in gold with earrings of diamonds bathed in gold,

and a small box of garnished gold, two rings, one with a diamond and the other with an emerald and two others with rubies. All of which came in a black ordinary trunk with two keys to register and manifest at the first port. And a quantity of reales of 500 pesos for my expenses in a linen bag to register in manifest in this form. I ask that Your Majesty register and manifest and I will pay the duties that are required and I request justice in this case, signed, D. Juan de Otalora".

PETITION : "Francisco de Pastrana and Pedro de Santisteban, we say: In conforming to the laws of Your Majesty I declare before the present scribe, I manifest three cases of reales that I brought registered and claimed to have two thousand pesos each. In the first one also contained were five gold bars and the numbers 2 and 3 contained 2500 pesos; and I also manifest two cases of worked silver with my mark, which came unregistered. I manifest a trunk with one gold tejo (disk) weighing 16 to 17 quilates, two dozen silver plates and one gold chain. And I am willing to pay the taxes and duties in reales for the case of bars and coins and 6000 pesos of which I register and of the worked silver and gold because I did not register it in Callao because of the hurry. And the said Pedro de Santisteban registered and manifested one trunk with two keys containing 1000 pesos and in another trunk with 700 pesos. These last two I declare belonging to maestro D. Antonio de Coca, and I am willing to pay the duties and taxes in reales. To Your Majesty we ask and plead to admit this manifest that we have made of the registry...Signed Francisco de Pastrano...Pedro de Santisteban".

The most interesting segment of the contraband story is that the Silver master of the San Jose fled with the registered cargo manifest immediately upon arriving on shore. The manifest was never found, even after Don Cristobal Velazquez was caught; "as the Maestro de Plata (Silver master), Don Cristobal Velazquez, escaped with it hidden in his pockets”(Lima 43, Letter dated July 2, 1631).

The reason for destroying this document is simple: If during the salvaging of the treasure, unregistered valuables were recovered, he would have been sentenced to a slave galley for ten years for allowing contraband cargo on board a Royal Ship. Excluding the testimonies of the survivors claiming to have lost large amounts of contraband, the Silver master's disposal of the cargo manifest is the most significant confirmation of the vast amount of unregistered treasure

brought aboard.

WRECK SITE DISCOVERY

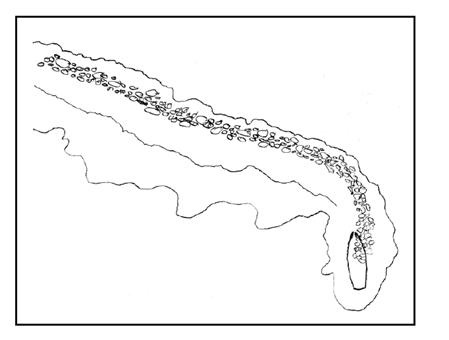

Personnel began searching for the wreck of the San Jose in 1997. Their investigations eventually led them to an isolated reef in the Bay of Panama southeast of the Perle Islands called Trollop Rock.

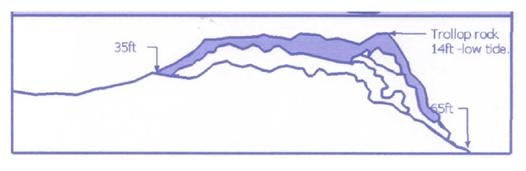

This isolated reef lies approximately midway in the channel between the Perle Islands and Point Garachine on the mainland. Approximately 1 mile in width; the reef is a rock and coral structure that rises up from the ocean depths and lies only 14 ft. below the surface at low tide.

Historical records indicate that where the ship struck the reef the water was 35 feet deep. This factor was used to begin the search of the reef to find the exact point where the ship ran aground and broke up. Considerable time and effort was expended and a very methodical approach using underwater gridlines was utilized to ensure that nothing was missed during the investigation. Remains of the ship were finally discovered on the far eastern end of the reef as depicted below.

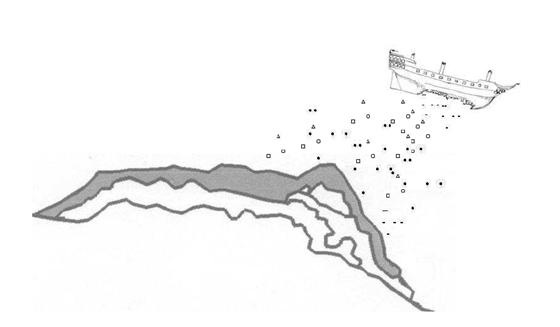

Historical research and field investigations confirm that the San Jose ran aground in 35 feet of water on the east end of Trollope Rock. She was stranded there for less than 24 hours during which time the passengers and crew were taken off by the Capitana.

During the night, ocean waves coming out of the southeast battered the San Jose and finally broke her up. The next morning when people arrived to begin removing cargo, the ship was nowhere to be found. The force of the ocean had torn the ship apart just above the keel due to the weight of the tons of silver bars lying in her hold. The rest of the ship was then driven northwest as cargo spilled from the hull.

During further investigations of the wreck site divers began recovering treasure and artifacts from the general area that were contained in pockets between the large rocks that make up the top of the reef. Items recovered from the reef including hundreds of silver coins, many dated 1629 or 1630 which are positive proof that this is the site of the San Jose. Other items recovered include several solid silver dinner plates and serving platters, a piece of a large silver bar, a base to a silver candelabrum, bronze cannonballs and broken pieces of majolica and olive jars. These were all items that came out of the ship after she had been broken apart by the ocean and the ruptured hull was sent drifting to the northwest over the reef and into deep water.

Two days later, the 3 main decks of the SAN JOSE, broken and shattered, were found drifting some distance to the North\Northwest of the reef. Most of the artillery was still lashed to the decks and was recovered. However, all of the cargo has spilled out on the northern side of the reef in water too deep for contemporary divers. (75 feet–125 feet)

CARGO ANALYSIS

Cargo carried aboard a Spanish Galleon can be divided into three distinct categories;

1. Treasure consigned to the King in the way of tax revenues and profits from enterprises owned exclusively by the Crown

2. Treasure being transported by private merchants, ships officers and crew

3. Treasure being smuggled to avoid paying the Kings tax of 20%

The San Jose carried a large shipment of treasure which was typical of the time. Records confirm a large amount of “registered” treasure which was properly listed on the ship’s manifest and taxes paid. Records also indicate that a great deal of “unregistered” or smuggled cargo was also being transported.

The official manifest lists the following registered cargo;

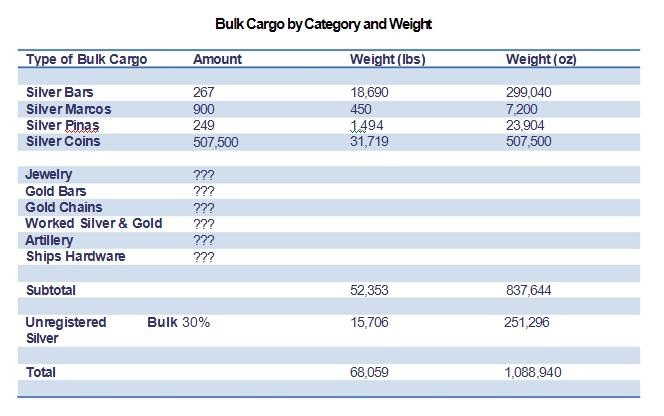

SILVER BARS

Registered - 1,417

Recovered - 1,115

267 silver bars still missing

Silver bars were produced in a variety of weights but most weigh an average of about 70 lbs.

SILVER COINS

Registered - 416boxes (8 Reales, 2500 per box) or 1,040,000coins

Recovered - 213

203 boxes are missing or 507, 500 coins

Coins minted at this time were the hand-made “cob” variety. The piece of eight or 8 reale is the most common denomination but large quantities of others were produced as well including, 4, 2, 1 and one half reales.

SILVER MARCOS

Registered - 2,500

Recovered - 1,600

900 marcos are missing

A silver Marco looks like a large fat poker chip and weighed1\2lb each. It was equal to 7 pesos (equal to 6, eight Real coins). In Potosi they were shipped 100 per box (1 box=50 lbs).

SILVER PINAS

Registered - 300

Recovered - 51

249 pinas missing

A Pina is a small silver bar. These bars weight around 6 lbs each. They were shipped to the King in small boxes of 12 bars. They're box weight and value was about the same as one large silver bar(72 lbs each). The registered treasure that’s still missing represents a total weight of approximately 25 tons.

MERCHANT CARGOS

There were over one hundred Merchant cargos registered onboard this ship. All were transporting merchandise to Panama or on to Spain to be sold as well as personal belongings.

This cargo contained;

1. Worked Gold and Jewelry-Rings, Broaches and Necklaces set with emeralds, diamonds and other precious stones, one merchant registered a 19 lb solid gold chain

2. Worked Silver and jewelry-Silver platters, plates, candelabras, forks, spoons, knives, tea pots

3. Personal Gold & Silver-Ingots, coins, tejo's, pinas and marcos

The literally thousands of pieces of personal property noted here were never recovered. The total value of the merchant's cargo alone has the potential of exceeding 50 million dollars. There are no records showing that any of these merchants ever recovered their belongings. They were hopeful that if the ship survived with part of the cargo they would have an opportunity to claim what was theirs. Most of this cargo was lost and never recovered; it remains on the bottom of the sea.

UNREGISTERED CARGO

During the colonial period, the King of Spain levied a tax of 20% on all goods shipped between ports. This tax resulted in the smuggling of treasure aboard ships being commonplace. There are many documented examples of this; every galleon that has been found in modern times has been found to carry varying amounts of unregistered cargo.

Including;

- Nuestra Senora de Atocha

- Santa Margarita

- La Capitana

- The galleons of the fleet of 1715

- The galleons of the fleet of 1733

- Nuestra Senora de los Maravillas

- Nuestra Senora de la Concepcion

Each of these ships carried varying amounts of unregistered cargo. The smallest amount, carried by the Atocha represented about 30% of her total cargo or one ton of unregistered treasure for every 2 tons listed on the manifest.

The most extreme example was La Capitana. Approximately 3.6 million pesos were listed on the manifest. However, after the Spanish completed salvage of the ship, 3 times the amount or over 11,000,000 pesos of cargo were recovered. The historical records indicate that a large amount of unregistered cargo was being carried by the San Jose. We can be certain that contraband was loaded aboard as a matter of course; however we also know that a large amount of cargo was transferred from the Capitana just before leaving port and was not listed on the manifest. For the purposes of estimating the total remaining cargo on the San Jose we will use the lowest figure of 30%, although the amount is in all likelihood higher.

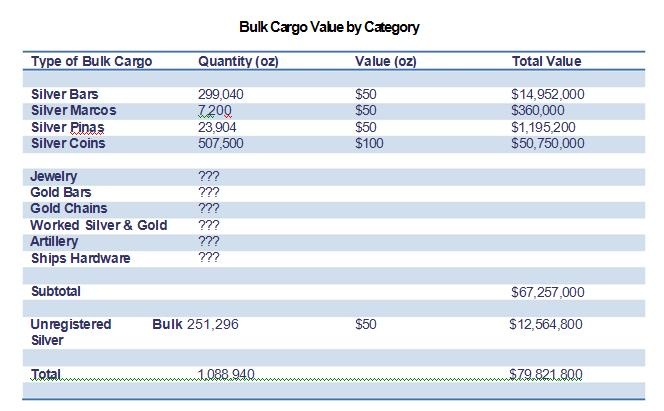

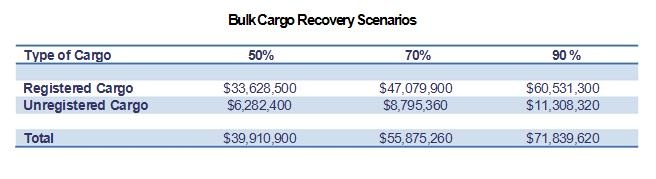

CARGO VALUATION

The following estimates of the value of the cargo of the San Jose and revenue distribution are based upon the following factors;

- All valuations are based on silver, no gold is factored

- All ingots are calculated at $50per ounce

- Silver coins are calculated at an average value of $100

- Unregistered bulk silver has been factored at 30% of the total recovery

NOTE: This valuation does not factor in the many high value items documented to be carried by the San Jose, including; gold bars, gold disks, gold chains, gold-gilded silver items, gold necklaces, earrings, brooches and crucifixes that were set with emeralds, diamonds and rubies, silver table settings and assorted worked silver objects. It also does not account for the value of the many types of artifacts that comprised the ship itself such as; artillery, cannonballs, swords, muskets, pistols, navigation instruments, medical instruments, ceramics and pottery.