Treasure 1622: Jewelry, Silver - Gold Coins, Pearls, Emeralds, Porcelan, Ceramics and Ancient Artifacts

History of the Santa Margarita

In September of 1622, a fleet of 28 ships, including the Santa Margarita, gathered off the coast of Havana loaded with riches collected from the many Spanish colonies throughout the ‘New World.’ This valuable cargo was desperately needed by King Phillip IV to pay Spain’s rapidly increasing debts. The Santa Margarita galleon was registered to be carrying 166,574 silver “pieces of eight” treasure coins, more than 500 ingots of silver and 9,000 ounces of gold.

In addition to registered legal cargo, passengers would often carry contraband wealth on their person and in their luggage to avoid paying a 20% tax to the Spanish crown. Within days, a violent storm wrecked five of the fleet near the Marquesas Keys in the Florida Straits. In total, 550 passengers and crew, including 142 from the Santa Margarita, perished in the brutal seas. All the treasure was lost to the bottom of a vast ocean.

This loss was a huge setback for Spain, whose world dominance at the time was reliant upon the riches from fleets returning

from their colonies. Immediate attempts to salvage the lost treasure were soon abandoned due to strong currents and further

storms scattering the treasure on the ocean floor. In 1624, Francisco Melian obtained the royal salvage contract for the sunken fleet. With the aid of Venezuelan pearl divers and his own invention, the diving bell, several hundred ingots and thousands of silver coins were found. However, multi-millions in treasures in the form of silver, gold and precious gems still remained lost at the bottom of the ocean. Over time, the Santa Margarita was forgotten, but not forever.

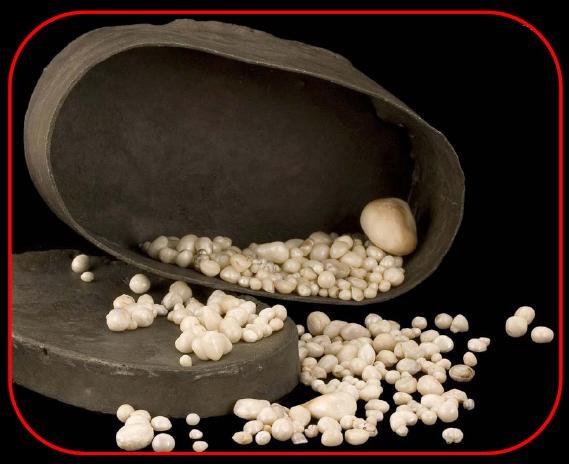

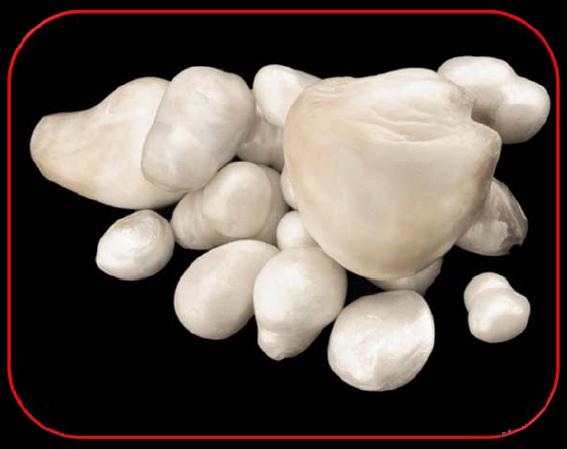

In 2007 and 2008, our associates recovered treasure from the site with an estimated value of $16 million consisting of gold chains and jewelry, a religious reliquary, silver coins and artifacts and gold bars. Two particularly notable discoveries: a lead box containing 16,184 rare and valuable natural pearls including one pear sized at 52 carats, one of the rarest natural pearls in the world and an exquisitely crafted gold chalice with an estimated value of more than $1,300,000.

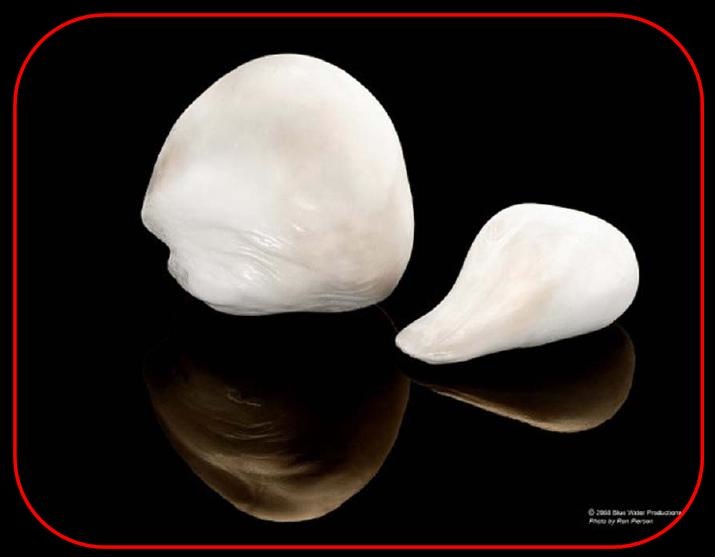

52 Carat Pearl

“Margarita” in Greek means pearl. The earliest 17th century attempt to locate and salvage the Santa Margarita was under taken almost immediately by the Spanish mariner Captain Gaspar de Vargas, who, knowing of their skills, sent for pearl divers from the Venezuelan island of Margarita to aid in the search.

Then, in 1624, Havana politician Francisco Melian obtained a royal salvage contract for the fleet galleons. This inventive risk-taker manufactured a device that allowed his divers to see and breathe while underwater. It was a diving bell, and it was this invention that allowed an enslaved diver to locate the first treasure of the Santa Margarita and win his freedom.

In 2007, the mystique of the ship’s name came full circle: Our Associates made an astounding discovery - one of Santa Margarita’s most extraordinary hidden treasures, a lead box containing 16,184 rare and precious natural pearls, not listed on the ship’s manifest. It is the expert opinion of Manuel J. Marcial that the pearls are Pinctada imbricata, and originate from the area known as “the pearl coast,” located along the north coast of Colombia and Venezuela, which includes the pearl island of Margarita.

The Gemological Institute of America has analyzed the pearls and believe they are the most unique collection anywhere in the world. It is important to note that pearls from these sources larger than 2 to 5 carats are extremely rare.

Gold Chalice

In the waters of the Florida Straits, where the 1622 Spanish galleon Santa Margarita met her fate, our Associates discovered an exquisite and exceedingly rare high karat gold, two -

handled drinking vessel, which the Spanish called a bernegal. No doubt the possession of an individual of highly prestigious lineage, the ornately engraved bowl arises from a threaded base

into eight lobes, with two beaded “question mark” handles. The artifact features a coat of arms engraved into the interior center, and while some promising clues to the arms’ identity have

surfaced, its definitive provenience remains unsolved.

In 1907, Leonard Williams published The Arts and Crafts of Older Spain, with 24 parts, or chapters, devoted to Gold, Silver, And Jewel Work. Following is an excerpt from his volumes

that gives a contemporaneous example of seals impressed on precious items:

“Quantities of jewellery and plate belonged to every noble household. For instance, the testament of the Countess of Castaneda (a.d. 1443) includes the mention of "a gilded cup and

cover to the same; a silver vessel and its lid, the edges gilt, and in the centre of both lid and vessel the arms of the said count, my lord…”

Gold Toothpick

In his book, The Toothpick - Technology and Culture, Henry Petroski quotes toothpicks as, “next to the wheel …man’s most universal invention.” He goes on to say that the Renaissance period was a time in which the toothpick, "alone or in a toilette set, exposed or in a decorated case, appears to have been worn and used most conspicuously and proudly.”

The Santa Margarita grooming tool is of high-karat gold and features a human profile, reminiscent of a ships masthead. This head emerges from the body of what might be a dragon or

other fantastical serpentine creature, uniting a toothpick at one extremity and an earwax scoop at the other. More than one expert expressed a perceived Asian appearance, and African

characteristics have been suggested as well - yet the overall effect has a New World feeling.

Because of the merging of artistic traditions that resulted from a rapidly shrinking world, it is conceivable that an artisan influenced by the craftsmanship of foreign cultures was the creator.

What is perceived today as a curious and eccentric artifact was at the time a symbol of cultured attention to hygiene, and when exotically crafted in solid gold such as this one, a success symbol

and conversation piece.

Gold Chains

It is very likely that many of the gold chains from the Santa

Margarita originated from China and the Far East and reached the Americas via the Pacific Manila galleon trade route.

While gold coins were relatively scarce in the Americas at this time, the value of money, whether silver, gold, or copper, was determined by its weight and not by its form.

Additionally, all subjects of the Spanish crown were required to

pay a 20% tax on their wealth – the Royal Fifth. They were not,

however, taxed on precious metals worn as jewelry; so, since gold in any form could be spent as money, and since payment of the Royal Fifth was unpopular, many had their gold crafted into chains that they could wear. The chain links typically were not soldered together, so a person wishing to buy goods or services could easily twist off a link and give it in payment. If the weight of the link was greater than the value of the purchase, the seller would cut off a portion and return it as change.

Gold Bars

In 1622, gold was commonly formed into bars and discs as

a standard way for shipping wealth from the New World to

Spain. The crown of Spain had not granted permission to create

gold coins in its New World Colonies and would not do so for

another decade.

Registered bullion of this nature had a number of official

markings: Circular stamps indicate that the 20% tax to the

king had been paid. A small bit (or bite) was removed by the assayer to test the purity of the gold. Then, the bar was

stamped with Roman numerals representing the purity in “karats,” (identical to the standards that we use today). Small dots following the Roman numeral each equal an additional 1/4 kt.

Some gold bars have been discovered with the karat markings scratched into them, rather than stamped. Gold bars discovered on 1622 fleet shipwrecks range from 10 to 23 karats. Gold and other valuable commodities were prone to smuggling, specifically to avoid taxation. It is when there are no markings whatsoever on bullion that we may be looking at smuggled pieces. In the case of the gold bar pictured here, it is long and thin and would have lent itself to being sewn into a lining of a trunk or cloth being shipped. It has been called a boot-bar because there is some anecdotal evidence that gold bars shaped this way could be slipped into a boot and smuggled.

Gold Reliquary

Another gentle fan to clear away the sand revealed a magnificent, fully intact religious reliquary, made of heavy, richly colored high karat gold, set with an oval of clear material, possibly rock crystal, providing a window into a recessed interior.

The recessed compartment would have been to hold a religious relic – which is the purpose of a reliquary. Examples of such relics might be the physical remains of a saint, such as a bone or a

fingernail, or some other object of devotion.

Reliquaries of the times were often illustrated with scenes related to the relic, which may account for what appears to be very thin gold foiling with markings and other as-yet unidentified

fragments within the interior compartment. The reliquary measures 1 ½ inches tall, 1 inch wide, 3/8 inch deep, and has a 3/8 inch ring-link for a chain.

Gold Ring

A high carat gold ring was set, not with an emerald as it appeared at first glance in the murky waters of the Florida Straits, but with a bead of green glass. The Spanish chronicler Bernal Díaz del Castillo, a soldier in the army of Hernán Cortés, documented numerous examples of the Spanish trading green glass beads

like this one with “the Indians” for gold, explaining that “the Indians thought they were chalchihuites, a green stone that they valued more highly than gold.”

Gold Emerald Ring

Archaeologist James Sinclair described the ring as a “wonderful example of the baroque style popular during this period,” adding, “while relatively simple and unadorned in design, the use of gold

and emerald speaks volumes as to the culture from which the owner and the object originated. Gold, then as now, was a symbol of status, so the owner of this antiquity was a high ranking and wealthy individual.”

Silver Coins

The Tierra Firma Fleet galleon Santa Margarita was carrying almost 150,000 silver coins when she sank in the Florida Straits in 1622. Most of the coins recovered originated from the mint of the city of Potosi; then a territory of the Viceroyalty of Peru, today of Bolivia, and most were minted during the reign of King Philip III.

Other mints and time periods are represented as well, but these are considered particular rarities within the Margarita collection.

Examples of rarities include coins with full or partial dates, Mexico City mint coins, and coins minted during the reign of King Philip II. Designated as “early” coins, those minted during the reign

of Philip II were already relatively old when the fleet sailed, and were produced during an era of great pride in craftsmanship and less urgency to make money fast. The men responsible for

producing them were skilled artisans—jewelers, silversmiths, and engravers who crafted coins that were centered, symmetrical, and finely detailed.

More rare still are coins minted in the reign of King Philip IV, whose rule began in March of 1621; coins displaying the legend of Johanna and Charles I, who ruled from 1504-1556; and the exquisitely lovely Lima, Peru, mint coins. Exceedingly rare specimens are one reale coins from any mint, coins from the Panama mint, the Santa Fe de Bogotá and Cartagena, Colombia mints; and a small representation of Old World minted coins, including the mints of Seville, Old Granada, Toledo, Madrid, and Segovia. These are the treasures within the treasure.

Gold Broach

Gold chain and broach would have undoubtedly have been the personal possession of passengers. The value of precious

metals were in their weight, but jewelry was not taxed the same way as bullion was, so smart Spaniards would have their gold jewelry -- a 1tax loophole.

Gold Bead

A number of these delicate beads have been found through the years on the Margarita wreck site. Similar items to these were recovered from the wreck of the Nuestra Senora de Concepcion, which was recovered off of the Island of Saipan. These delicate objects were likely created in China for the European market.

Other evidence of the far flung reach of the Spanish Empire is

found every once in a while on the sites in the form of Chinese

porcelain fragments.

Gold Square

Discovered in February, 2009, a gold “flowerette” of jewelry, and an intriguing square of decorative hammered gold, wafer-thin, no more than 1/2 inch in diameter.

Examples of similar hammered and chased gold jewelry, insignia and regalia, which were produced by professional goldsmiths, can be found in collections of Asian and African artifacts. Their designs were often meant to represent familiar proverbs or maxims, which may explain the design motif and irregular sequence of raised lines on the outer perimeter of the artifact.

The gold flowerette is one of four six-pointed gold floral settings discovered, each of which may have once held a precious gem. Over the years, a number of these ornaments have been found on the Margarita site.